Arya, 29 F, Unmarried, SBI Fellow – Took a Ticket to The Unknown

Visual Journalist| Producer |Video Editor|Sexuality Educator|Rural Development Fellow

At twenty-nine, while most of my friends wore henna-stained hands and gold-threaded saris, I found myself clutching a ticket to a village I had never heard of. My mother’s voice echoed in my mind; she always used to say, “Every choice you make has a consequence.” For her, that meant the impending cost of another year unwed, another whispered question at family gatherings. For me, it meant something entirely different: The Unknown.

As a visual journalist, I had a career I loved. I was good at it. My days were spent researching, capturing, and creating stories, translating emotions and news bytes into 24 frames per second. But over time, a sense of monotony started to seep into my routine. Every day, I passed by the same metro pillar, in Palarivattom, and that pillar came to represent my life as solid, stable, and utterly immovable. I felt stagnant, restless, yearning for something else, though I didn’t know what to do next.

One afternoon, over coffee, a colleague mentioned the SBI fellowship. It was an opportunity to work with communities, to learn, and where my work could mean something deeply personal to those I would be working for. The moment I heard about it, I knew I wanted it. I applied, got selected, and felt that rush of excitement I hadn’t felt in ages.

When I broke the news to my family, it was as if I had announced moving to Mars. My mother nearly fainted. “A fellowship? At your age?” she exclaimed, her voice filled with disbelief. At 29, she reminded me, that women were supposed to be married, not packing their bags to head to a random village that too in some other state of the country. Turning 30 unmarried was, in her eyes, a ticking time bomb that would rob me of future prospects and keep younger suitors at bay. She clung to the idea that marriage, was my only path to stability and respectability.

My parents eventually agreed to see me off to Madurai, where my orientation was held at the Dhan Academy. My mother’s goodbye was filled with reassurance that I could come home any time at the first sign of discomfort. But deep down, I knew this was my chance to break free from my comfort zones, and expectations, and even from the grip of my mother’s love and worry.

After Madurai, I was assigned to Koinpur, Odisha, where I would work with Gram Vikas, a rural development organization.

Gram Vikas, Koinpur Campus

I traveled there with my co-fellow, Shazia Masood, a spirited woman from Kashmir. If I had stayed in Kerala, I’m not sure I would have ever had a Kashmiri roommate, nor would I have met the diverse group of people who would soon become my tribe. There was Kaumudi from Maharashtra, Itishree from Odisha, Aravind from Telangana, and Joel, a fellow Malayali from Mumbai. Life in Koinpur slowed down significantly. Gone were those tiring Mondays; in their place, I found a steady rhythm that made me feel present and connected.

From left Arya, Shazia, Itishree, Aravind, Chandan, Lalit, Arya, Dauda, Joel, Arya, Kaumudi, Shazia

The beauty of Koinpur, the quiet roads, lush green hills, and warm, welcoming people brought me a sense of calm.

Yet, it wasn’t all smooth sailing. I couldn’t understand a word of Odia beyond ‘macha’ (fish) and ‘ondo’ (egg). My insecurity whispered that no one liked me, a feeling I often had when meeting new people. But, as the days rolled by, I began to find my footing. By the third month, children would come running, calling out, “Deedi, aaji ame konu seekhiba?” (“Sister, what will we learn today?”) Little by little, I was building connections, and each step made me feel more at home.

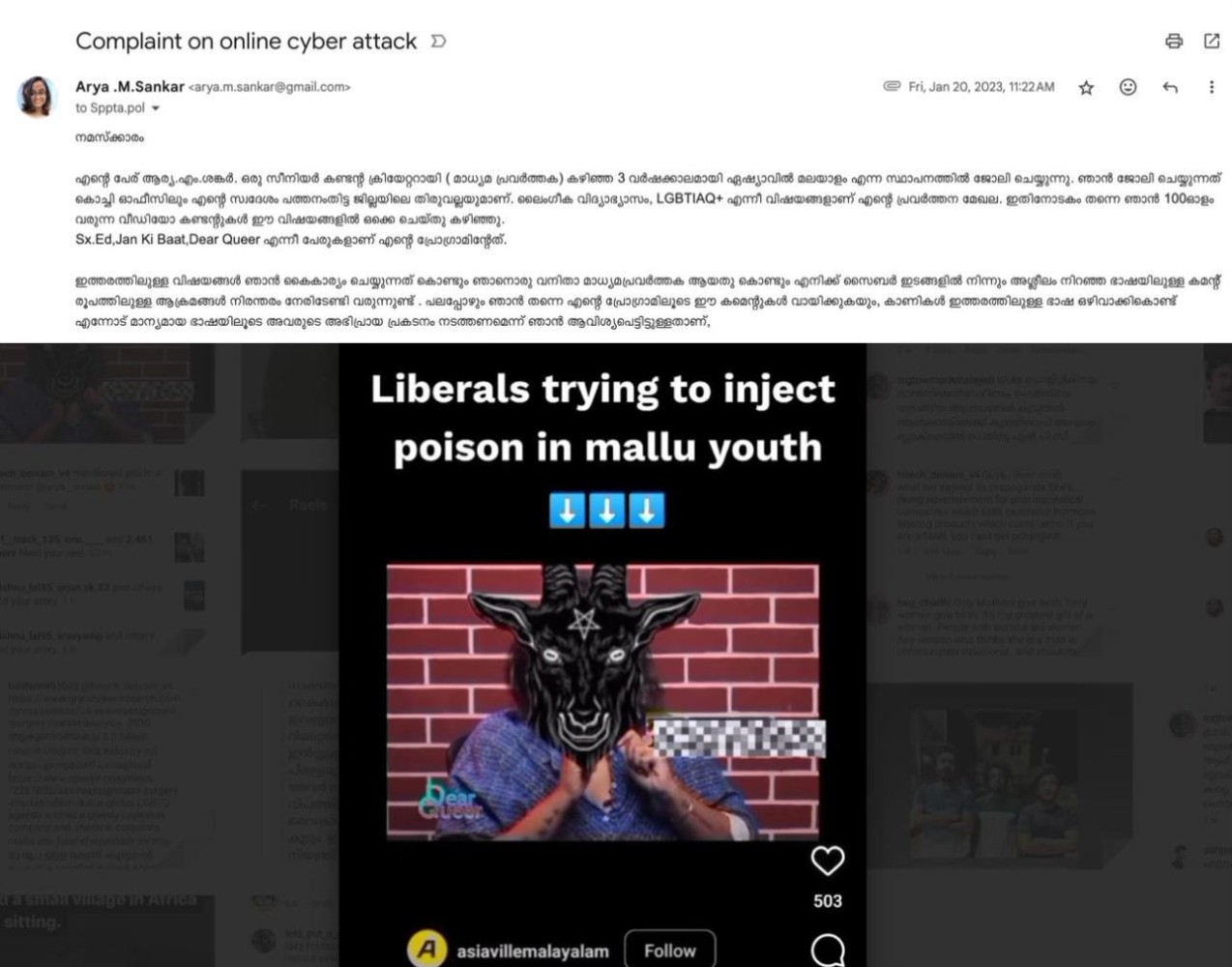

My project was on sex education, an area I had covered as a gender journalist in Kerala. In Kerala, my work on topics like gender, sexuality, and relationships had often met with harsh online backlash. I have seen my face morphed with that of a goat in videos where I discussed such topics.

The so-called educated crowd of Kerala, the smart voices behind screens threw insults and threats whenever I tried to address these issues in public. I anticipated a similar reaction in Odisha, fearing rejection or opposition. However, the response I received was surprising.

Women in Andergai, Kalinga, and Raisingi, the villages I worked in, welcomed my ideas. Women and children were my stakeholders in the project I was working on. Whereas, the men were a bit curious about what I was discussing with the women and children. Eventually, as I became more familiar with them, a few men from the village of Andergai kind of understood the purpose of my work. They never questioned the sessions I conducted, and by the end of my project, they responded with, ‘Ame be sikhaibo deedi’ (Please teach us too, sister). But by then, I didn’t have enough time to start with them. I was too skeptical about how the community would respond to the subjects I was discussing, which is why I began with women and children.

Through my sessions, I spoke with the women about our bodies, safe sex practices, and healthy relationships. These conversations were not just about imparting knowledge but about opening up a new world to women who rarely had access to such information. In these villages, early marriages were common, and each household had three to five children, tying women to their homes and limiting their world to kitchen walls. I met women who had never known the luxury of resting during the day because they were always tending to the needs of their large families.

For many of them, their dreams were given up because of early marriage.

One of my closest friends in the community, whom I call Deedi, told me, “If we hadn’t married so young, maybe we could have had the independence you have today.” Those words stayed with me. Her story mirrored countless others, where marriage was a boundary instead of a foundation. Through our talks, I started to see a glimpse of change. Deedi and others told me that they would not allow their daughters to repeat the same story. They wanted their girls to have choices, to understand their worth, and to build lives beyond societal expectations.

As my fellowship drew to a close, I prepared for my final presentation with my deedis. These women, who had once been strangers, had become my family. They seemed fierce, capable and they started dreaming again. One of my deedis even registered for the 10th standard exam that she had left behind. When they told me they wanted to ensure their daughters grew up free to pursue their own paths, I felt a deep sense of hope and responsibility, knowing that a positive outcome was yet to come and that it might take time.

From left Sandhya Deedi, Sumitra Deedi & Surabhi Deedi (pink saree)

Reflecting on my journey, I realized how transformative the last year had been. At 29, I had chosen an unconventional path, one that was met with skepticism, concern, and societal disapproval. But by the time I turned 30, I felt like someone more healed, more resilient, a version of myself that I hadn’t known was possible. To mark this change, I inked a small tattoo on my left arm, the name “Koinpur” paired with a semicolon, a reminder of the chapter I paused on, and then bravely continued. I celebrated my 30th birthday in Koinpur instead of wedding bells I was surrounded by the people who had become my tribe, their voices loud and joyfully screaming, “Arya hogayi 30, hum karengi party!”

Choosing this fellowship over marriage was not just about career growth; it was about breaking free. It was about embracing the uncertainty, the challenges, and the profound beauty of connecting with people who would have otherwise remained distant from me.

<3 <3

It was about allowing myself to grow on my own terms, and through that, learning that true fulfillment often lies in the paths least expected.

To my mother, and to all those who saw marriage as the ultimatum of success and stability, I say this: sometimes, a woman’s path to fulfillment doesn’t come with a ring or a wedding ceremony. Sometimes, it’s the choice to explore, to serve, and to truly live that brings the deepest sense of joy and purpose. As I move forward, I know that this journey of self-discovery will continue to shape me in ways I have yet to understand.

After 1,000 commands, this is one of the most likable images that ChatGPT generated. While the girl doesn’t exactly resemble me, it captures the essence of what I wanted to convey and that’s how this image earned its spot!